Designing Dignity: Leading Disability-Inclusive Futures in the Built Environment

South Africa’s built environment stands at a critical inflection point. As the country intensifies its efforts to transform cities, towns, human settlements, and social facilities it must confront a fundamental truth: our infrastructure, the buildings we design, the public spaces we shape, the transport mobility systems we imagine, either enables dignity and participation, or it deepens exclusion. The Council for the Built Environment (CBE), guided by its theme “Amplifying the Leadership of Persons with Disabilities for an Inclusive and Sustainable Future,” recognises that the built environment is not neutral. It carries the imprint of the professionals who conceive, plan, design, and regulate it. This places a profound responsibility on architects, engineers, construction managers, planners, and quantity surveyors to ensure that the environments they create do not inadvertently marginalise people living with disabilities, but act as instruments of liberation, opportunity, and full citizenship.

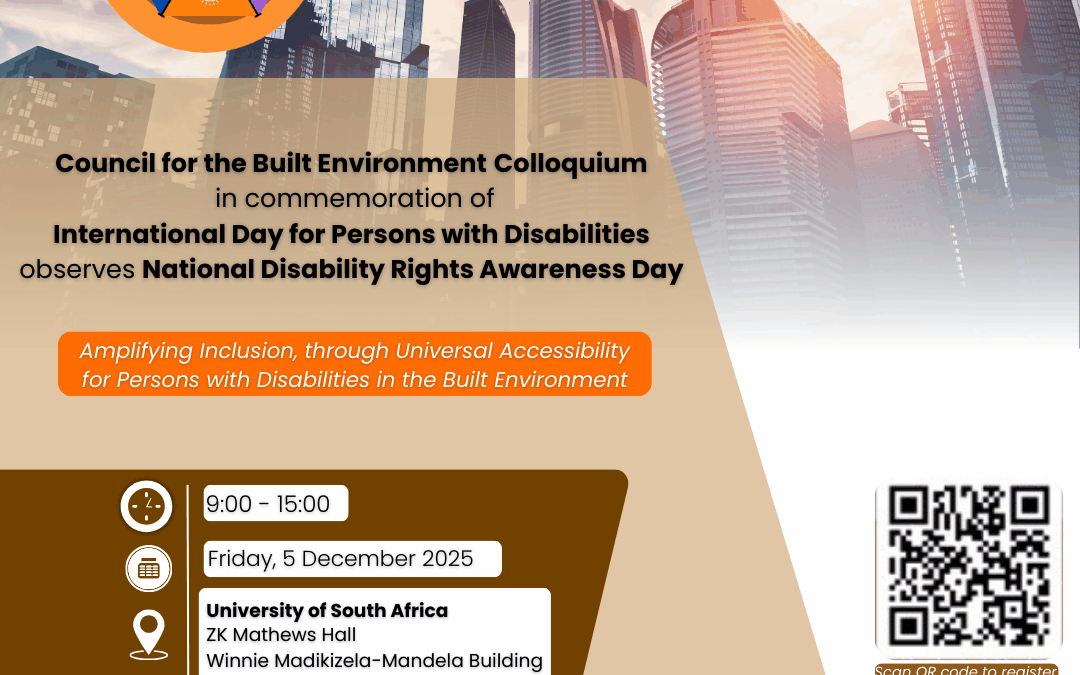

In South Africa, persons with disabilities continue to face structural barriers: inaccessible clinics and schools, public buildings without ramps or lifts, unsafe sidewalks for users of mobility aids, transport systems that do not accommodate diverse needs, and public facilities with signage that excludes those with low vision or hearing related disabilities. These barriers are not simply operational oversights. They represent failures in design thinking, regulatory compliance, professional ethics, and, most importantly, the meaningful inclusion of persons with disabilities in decision-making processes. The CBE 2025 Built Environment Annual Colloquium asserts that the future of the profession must be built on an unwavering commitment to human-centred and rights-based design, where disability inclusion becomes a default requirement rather than an afterthought.

This year’s national theme, “Creating Strategic Multisectoral Partnerships for a Disability-Inclusive Society,” reinforces that disability inclusion cannot be achieved by the built environment professions alone. It requires deep collaboration between government, professional councils, voluntary associations, disabled persons’ organisations, academia, private industry, and communities. Partnership is no longer optional; it is the engine that allows ideas to move from policy to practice. For built environment professionals, this means engaging with disability advocacy groups when developing design briefs, working with social development and health sectors on universal access priorities, collaborating with local government on inclusive urban management systems, and co-producing infrastructure solutions with the very communities that will use them. These partnerships shift the narrative from designing for persons with disabilities to designing with them, affirming their leadership, expertise, and lived experience as essential to shaping a truly inclusive future.

A strengthened disability-integrated approach also requires that we explicitly confront gender inequality and its intersection with disability. Women and girls living with disabilities often face multiple, layered forms of discrimination and exclusion. Poorly lit and poorly maintained public spaces heighten their risk of violence. Inadequate public transport systems limit their mobility, economic participation, and educational opportunities. Built environment professionals cannot ignore these realities. By adopting an intersectional lens, built environment professionals must shift from compliance-driven design to transformative design.

Critical to this transformation is acknowledging that persons with disabilities must not only be considered as users of infrastructure but must also be recognised as leaders, experts, innovators, and drivers of change across the built environment. Their leadership disrupts long-held assumptions about what constitutes “normal” design and introduces new ways of understanding accessibility, usability, and human experience.

The professionalisation agenda led by the CBE further places disability inclusion at the centre of ethical and technical excellence. A capable state requires capable built environment professionals, professionals who are not only technically proficient but are socially conscious, empathetic, and committed to safeguarding the rights of all citizens. The shift towards disability-inclusive infrastructure is therefore not simply a moral imperative; it is an essential component of building a resilient and sustainable South Africa. Accessibility is a prerequisite for economic participation, for education, for health, for safety, and for the dignity and self-determination of individuals and families. When accessibility improves, entire communities benefit, parents pushing prams, older persons, people with temporary injuries, and individuals with chronic illnesses. Inclusion is not charity; it is good design, good governance, and good economics.

The commitment to disability inclusion must be visible in infrastructure audits, procurement processes, project inception reports, budget allocations, and monitoring frameworks. It must shape the conversations that engineers have at drafting tables, the questions planners ask during site visits, the solutions architects imagine for public facilities, and the quality assurance processes applied by regulators and certifiers. Most importantly, it must be embedded in how the sector values and elevates the leadership of persons with disabilities.

It is one where women and girls with disabilities move freely and safely. It is one where partnerships across sectors create infrastructure that reflects the diversity of South African society.

In amplifying the leadership of persons with disabilities, the CBE is not merely advocating for better design; it is calling for a reimagined profession, one capable of transforming society through inclusive, ethical, and future-oriented practice